Shane Farritor, Ph.D. (left) and Michelle Eggen.

by Tyler Mueller, UNeMed

OMAHA, Neb. (October 19, 2015)—Professionals recounted their journeys through to their career path job and offered advice during a panel discussion before an estimated audience of 43.

For many of the speakers, the most important advice they could offer was to know what you wanted to do as early as possible and know how to take skills and make them applicable to other areas.

The panel was a part of UNeMed’s Innovation Week, which continues today with “Surviving Your Stupid, Stupid Decision to Go to Grad School,” by Adam Ruben. To learn more about other Innovation Week events, go here.

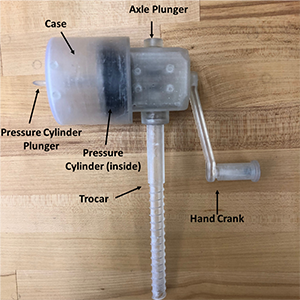

On Monday, Shane Farritor, Ph.D., opened the panel discussion. He began his career as an academic in space robotics and space engineering. But it was difficult to make a living in the field. Dr. Farritor saw a bigger need for biomedical devices. When he met UNMC surgeon Dmitry Oleynikov, M.D., nearly 10 years ago, they created Virtual Incision and started collaborating on surgical robots. He know devotes half his time to managing the company.

Michelle Eggen got started as a medical writer when she saw a job posting for someone with a science background who could write. Eggen was working on her Ph.D. but dropped out to continue working in the industry. While not recommending dropping out, Eggen said a Ph.D. isn’t necessary to be successful.

Tyler Martin, Ph.D., wanted to be an infectious disease scientist after spending four months in a Zaire hospital. After working in an area with an infant mortality rate of 50 percent, he gained a new perspective on what he wanted to do with his life. He has worked for the past 20 years mainly with vaccines and gene therapy.

Tyler Martin, Ph.D., (left) and Lisa Bilek, Ph.D.

Lisa Bilek, Ph.D., moved into industry work when she realized she said she “hated bench work.” She became a medical science liaison, where she and a group of individuals worked to form relationships with other people or groups in the same scientific area. Dr. Bilek works to answer questions on a field of study or help a researcher gather funds to develop a technology.

Austin Jelcick, Ph.D., worked for a small startup, dabbling into everything from vendor relations to public relations and to research and strategic sourcing as a project manager. Now as a director of business strategy, he uses his education and experience to “work as a collaborator, rather than a service provider for researchers.”

For finding a job, Dr. Bilek suggested a career coach. A career coach helped her make a resume specific to each job application, and they taught her interviewing skills and how to brand herself.

Dr. Jelcick’s advice when looking for jobs was to take the skills from working in the lab and make them relatable to the job. Dr. Jelcick also suggested investigating a company to find out who to talk about job opportunities.

Dr. Martin suggested starting out at larger companies. Larger companies have better training compared to smaller startup companies, Dr. Martin said. Smaller companies represent more risk for people with less experience in the field.

“With smaller companies like mine, I throw you in the deep end,” Dr. Martin said. “If you swim, great. If you don’t, sorry.”

Eggen said to know what you want to do as early as possible and know what’s most important. There are a lot of factors when it comes to jobs, such as title, money, and the location. Knowing early which of these is most important will definitely take you farther, Eggen said.

Austin Jelcick, Ph.D.

Dr. Jelcick ended the discussion stressing the importance of hard work and the right attitude. While in undergrad, you simply complete your coursework with passing grades to graduate. In grad school, it’s not as easy.

“There is no longer a light at the end of the tunnel but rather a tunnel where the light is where you make it,” Dr. Jelcick.

He added: “You can be blinded by this sense of entitlement. You’ve worked so hard for so long that you deserve to have a good-paying job when you finish. The fact is, you don’t deserve anything. You deserve what you make of it.”