by Amanda Hawley, UNeMed | December 1, 2015

Trying to convey the significance of science without proper communication skills is like asking a friend to assemble an IKEA chair, but giving them the instructions through interpretive dance.

Good luck.

Publishing and presenting scientific discoveries in only field-specific venues will limit the impact and greater purpose of publicizing these advances.

But why should science enthusiasts give a damn?

Information provided by media influences the opinions and ideologies of the public, which in turn shapes the political climate. The public’s perception of science and research—be it positive or negative—effects the decision makers in our nation’s capital.

Information provided by media influences the opinions and ideologies of the public, which in turn shapes the political climate. The public’s perception of science and research—be it positive or negative—effects the decision makers in our nation’s capital.

Science supporters need to ignite a change in the public perception to prioritize education and research programs. One way to accomplish this shift is by improving the current strategies of informing and educating the general population.

Learning of new discoveries should not require an advanced degree in science or a decoder ring to translate scientific jargon.

Communicating these scientific advances should be applicable to all. And I mean all—right down to story time, sitting crisscross-applesauce surrounded by sticky fifth-graders.

If researchers are frustrated with the lack of funding or diversity within the sciences, perhaps it’s time to look in the mirror. The public’s lack of scientific understanding and appreciation stems from the negligent and an improper education.

Vocal, non-science experts create distrust and doubt, misleading the public away from science, as seen in the debates on vaccines and global-climate change.

A well-known U.S. scientist Neil deGrasse Tyson, PhD, said in a November 2007 Point of Inquiry interview: “How is it that access to science could be so high, yet it appears that science literacy in the population has made only marginal gains, if at all? Some would say its reverted to superstitious over the rational analysis of the real world in which we live.”

He added: “The more I recognize that things might be going backwards, the more I would have to admit that I am failing in what I am trying to do…create some increased level of science literacy in the electorate.”

Despite the enormity of resources just a click away, an inaccurate public perception of science is the annoying pop-up windows you can’t close.

Adam Ruben, PhD, from “Outrageous Acts of Science” on the Science Channel, gave a talk during UNMC’s 2015 Innovation Week titled “Public Perception of Science.” He listed examples of the public’s ill-informed response to scientific discovery like cloning animals, vaccines, and the joke campaign against dihydrogen monoxide (a.k.a. water, H2O).

Adam Ruben, PhD, from “Outrageous Acts of Science” on the Science Channel, gave a talk during UNMC’s 2015 Innovation Week titled “Public Perception of Science.” He listed examples of the public’s ill-informed response to scientific discovery like cloning animals, vaccines, and the joke campaign against dihydrogen monoxide (a.k.a. water, H2O).

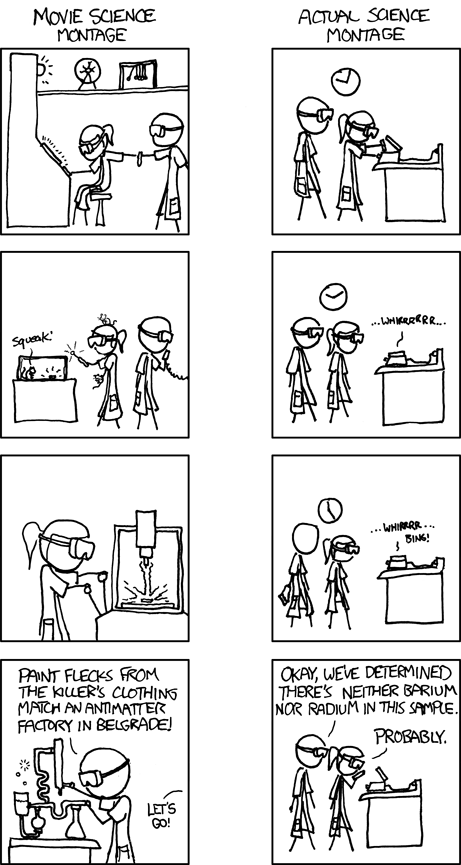

Dr. Ruben explained how the portrayal of scientific discovery can be alluring to audiences, yet entirely misleading. This deception further weakens the relationship between scientists and the public.

Why are scientists generally identified as being unapproachable, elitist, or stereotyped as mad? Sorry scientists, we are as relatable as porcupines and pineapples.

Why are scientists generally identified as being unapproachable, elitist, or stereotyped as mad? Sorry scientists, we are as relatable as porcupines and pineapples.

The stereotype of scientist was no better depicted by a class of seventh-graders. The class was asked to draw and describe a scientist before and after meeting an actual researcher. In the first drawing, the majority of children depicted a nerdy-looking, bald man wearing a white lab coat. After meeting an actual scientist, they drew normal-looking people without the stereotypical identifiers.

Perhaps the issue of science illiteracy boils down to the public’s inability to relate to scientists or connect to science overall.

A common problem in many relationships is improper communication.

With the current communication strategy applicable to only a miniscule percentage of the population, I fear scientific researchers will further become estranged from the public and hinder the support of scientific innovation.

So frankly my dears, you all should give a damn!