by Charlie Litton, UNeMed

OMAHA, Neb. (March, 25, 2015)—Long before Nebraska’s largest city landed on any national top 10 lists for its startup scene. Long before the state carved out incentives and initiatives to promote high-tech business growth and development. Long before anyone thought Nebraska was a good place to start a biomedical company, there was Randy Jones and his ideas for better MRI scanners.

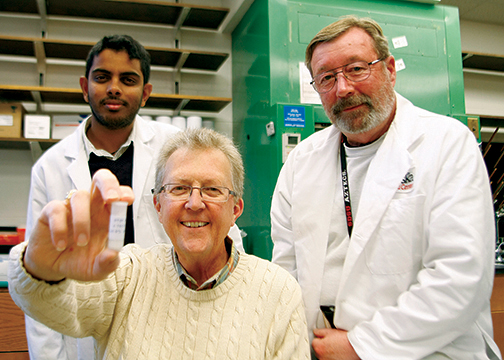

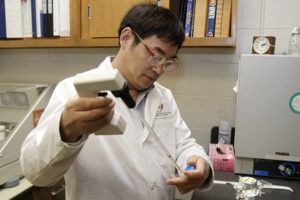

ScanMed founder and CEO Randy Jones, PhD, looks over one his prototypes for an MRI scanning coil that will help physicians finally get detailed images of a patient’s lung tissue. (Photo: Charlie Litton)

Jones, who holds a doctorate in electrical engineering, founded ScanMed of Resonance Innovations in his basement as a four-man operation in the mid-1990s: Back when most other medical device companies were running to biomedical hubs like Cleveland or Minneapolis.

Jones stuck with Nebraska, and it’s finally starting to pay off.

In the last three years, his business has exploded to a multimillion dollar company with a growing national reputation for rebuilding, repairing and developing new and innovative coils for magnetic resonance imaging scanners, or MRIs. After 10 tumultuous years of innovations, breakthroughs and setbacks, ScanMed’s next generation of coils—and its burgeoning repair service—has finally turned the proverbial corner with more than 30 employees and a three-year facility expansion that has grown from 5,000 to 15,000 square feet.

Already, that space could soon start feeling cramped.

“All the conditions were right, finally,” Jones said. “It’s still a little underutilized, which is good because we’re still growing. And this year is going to be a tremendous growth year.”

Jones said the company enjoyed a 99 percent growth in 2013, and used that momentum to expand operations in 2014. In 2014, ScanMed cut into its growth rate with more than $1 million investment in product development and additional hardware.

A key piece of nearly exponential growth was a 2012 buy-in from the state. With a $500,000 matching seed investment, ScanMed became the first company to receive investment funds from Invest Nebraska, a public-private venture development organization funded in part by the Nebraska Department of Economic Development. Invest Nebraska focuses on fostering high-growth, high-paying industry startups and small business in Nebraska.

“The fact that we got a lump sum of real capital was real helpful,” Jones said, “because we were able to buy, or at least put down deposits on, a lot of necessary equipment to get to our next growth plane.”

Just two-and-a-half years later, in December 2014, a private strategic investor bought out Invest Nebraska’s interest—at an undisclosed, but tidy profit—and sent ScanMed sailing into the future.

Jones said the infusion of cash from Invest Nebraska and other investors helped ScanMed install a 3D printer and one of the nation’s few fully-functioning MRI scanners not attached to a hospital or university. The scanner alone—a used version of General Electric’s most popular model—cost about $600,000 to purchase and install, and Jones said he already has plans to add to his arsenal a popular Siemens version.

Having a scanner on-site frees Jones and his team from renting scanner time at a local hospital. Now, they can test at will the kind of innovative products that are at the core of Jones’ passion for the business.

But the business wouldn’t have survived this long without a repair service division that “carried” ScanMed during a downturn in the medical device industry in 2008 and 2009.

“There were almost no new equipment purchases in almost two years,” Jones said “What does that do to a medical device company? You just die and go away.”

ScanMed paid the bills and survived the lean years with an MRI coil repair service that now fulfills orders from across the world. The repair service accounts for about half of ScanMed’s business, but it was the innovations that inspired ScanMed’s beginning. And it appears more innovation will pave its future.

ScanMed has developed innovative coils that focus an MRI’s powerful imaging technology on specific body parts. ScanMed products can show physicians problems in areas that previously remained elusive. Jones said he has an imaging coil that can accurately detect prostate cancer, and another that can read the notoriously difficult-to-see soft tissue in the lungs—which could have a profound impact on how physicians treat and diagnose chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, or COPD.

“Having survived all the nasty stuff that we have survived,” Jones said, “I feel pretty comfortable with where we are.”

disease (COPD) detector in the largest ongoing clinical study of COPD exacerbation. The University of Nebraska at Omaha’s

disease (COPD) detector in the largest ongoing clinical study of COPD exacerbation. The University of Nebraska at Omaha’s

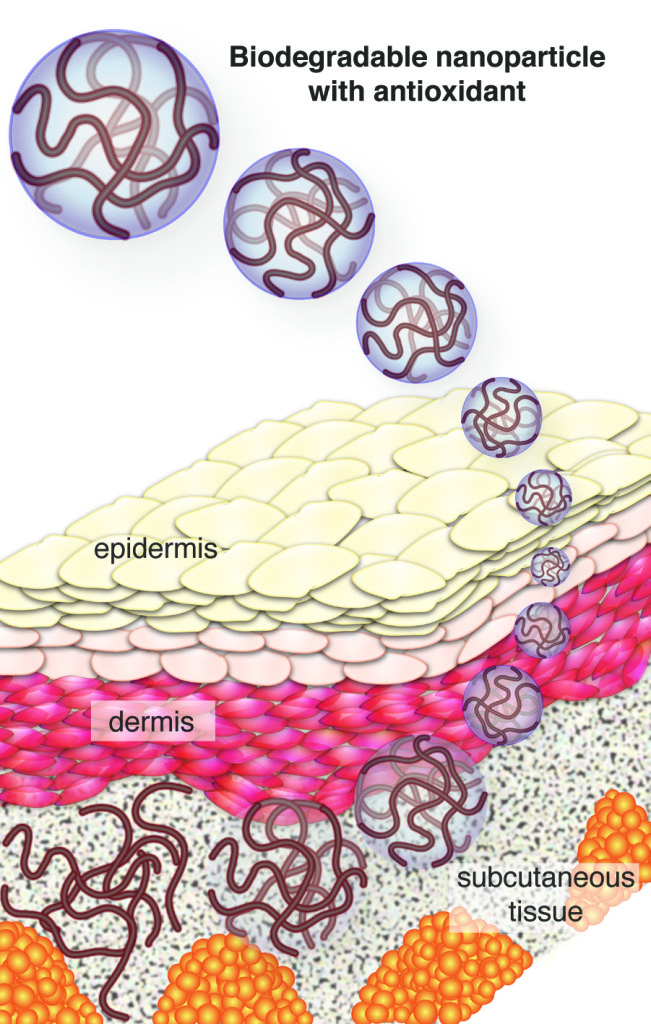

Amarnath Natarajan, PhD, received a University of Nebraska Proof of Concept grant to further his research on “

Amarnath Natarajan, PhD, received a University of Nebraska Proof of Concept grant to further his research on “ The study, completed by nationally recognized consulting firm Tripp Umbach, shows that the Med Center not only contributes to the state’s well-being in health care, but also is a major player in driving its economy, said UNMC Chancellor Jeffrey P. Gold, M.D.

The study, completed by nationally recognized consulting firm Tripp Umbach, shows that the Med Center not only contributes to the state’s well-being in health care, but also is a major player in driving its economy, said UNMC Chancellor Jeffrey P. Gold, M.D. His talk, “A New Paradigm for Engaging the War on Infectious Diseases,” is set to begin at noon on Tuesday, Feb. 17. Mirsalis is an internationally recognized expert at developing drugs for infectious diseases. He is expected to discuss efforts to overcome recent cutbacks in funding for research and development with a growing trend toward private-public partnerships. He will focus on the growing need for vaccines and therapeutics, and will present new models for discovering and developing them.

His talk, “A New Paradigm for Engaging the War on Infectious Diseases,” is set to begin at noon on Tuesday, Feb. 17. Mirsalis is an internationally recognized expert at developing drugs for infectious diseases. He is expected to discuss efforts to overcome recent cutbacks in funding for research and development with a growing trend toward private-public partnerships. He will focus on the growing need for vaccines and therapeutics, and will present new models for discovering and developing them.

We have been spoiled by the good fortune of having only happy news to share in the realm of medical research and development, so we were unprepared for the harsh reality of saying goodbye to our friend and colleague, Jack Mayfield, who suddenly passed in late October. It was a tough, bitter pill to swallow, and one we still lament today. The profound loss was a seismic event felt by everyone in our office, many others in the university system and even the region. By comparison, the remaining items on the following list seem trivial.

We have been spoiled by the good fortune of having only happy news to share in the realm of medical research and development, so we were unprepared for the harsh reality of saying goodbye to our friend and colleague, Jack Mayfield, who suddenly passed in late October. It was a tough, bitter pill to swallow, and one we still lament today. The profound loss was a seismic event felt by everyone in our office, many others in the university system and even the region. By comparison, the remaining items on the following list seem trivial. 2.

2.

4.

4.  6.

6.  By all our measures, the 2014 Shareholder Meeting was a runaway success. While the meeting served several notable purposes, it also marked the first public announcement that UNeMed was expanding its operation to China with the establishment of

By all our measures, the 2014 Shareholder Meeting was a runaway success. While the meeting served several notable purposes, it also marked the first public announcement that UNeMed was expanding its operation to China with the establishment of  8.

8.  National media extensively covered the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s involvement with the treatment of Ebola patients who were infected while helping people in stricken Africa nations. When we first heard that Richard Sacra would be our first Ebola patient at the now world-renown biocontainment facility, we shared many of the conflicted emotions that everyone felt. But upon final examination, we were all proud to be associated with an institution that had the people, training, facilities and expertise to handle such patients. And as Joe Runge elegantly pointed out in this blog post, the best hope of containing the outbreak is to care for those frontline caregivers who bear the brunt of the risk as they try to save lives and comfort the afflicted.

National media extensively covered the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s involvement with the treatment of Ebola patients who were infected while helping people in stricken Africa nations. When we first heard that Richard Sacra would be our first Ebola patient at the now world-renown biocontainment facility, we shared many of the conflicted emotions that everyone felt. But upon final examination, we were all proud to be associated with an institution that had the people, training, facilities and expertise to handle such patients. And as Joe Runge elegantly pointed out in this blog post, the best hope of containing the outbreak is to care for those frontline caregivers who bear the brunt of the risk as they try to save lives and comfort the afflicted. 10.

10.